Back in 1987, a young Brian Schmidt walked into an interview at one of Chicago’s biggest pinball machine manufacturers, Williams Electronic Games.

“There was a job opening for someone who could program assembly language and also write music,” Schmidt, a senior lecturer for DigiPen’s BA in Music and Sound Design program, says. “So, you know… there weren’t a lot of people around who could do both at the time.”

Having recently graduated with two bachelor’s degrees from Northwestern University (one in computer science and another in music), and with a master’s degree in computer applications in music on the way, he was uniquely suited for the position. Even so, the interview concluded with a challenge he didn’t anticipate — one he’d inadvertently been preparing for his whole life.

“They took me into the back room and asked me if I wanted to play this unreleased pinball machine,” Schmidt says. “I’ve always loved pinball. My mom used to get mad at me for ‘wasting’ my whole allowance on pinball machines. I later found out that the fact that I was a really good pinball player was a big factor in me getting hired.”

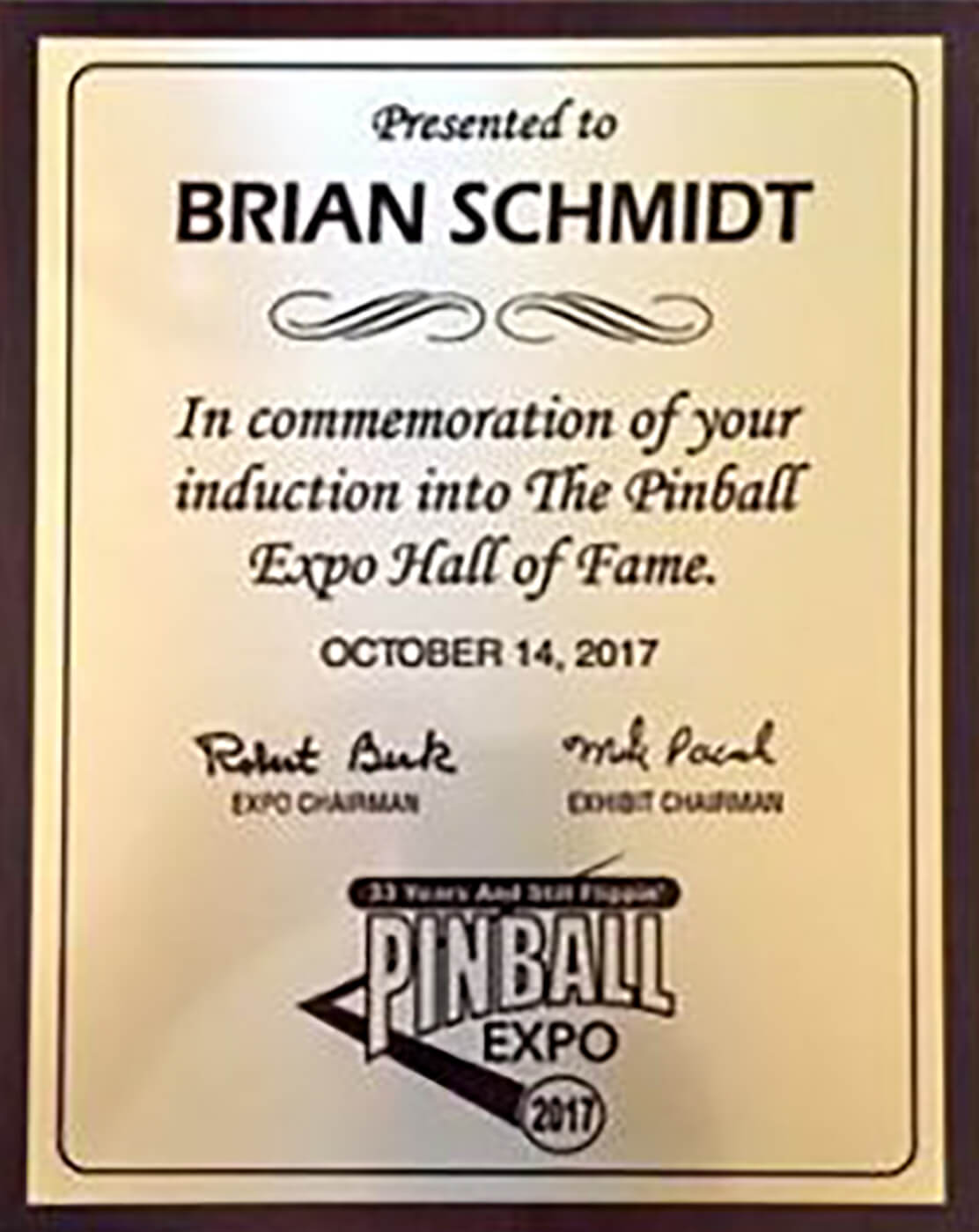

Thirty years later, on October 14, Schmidt was inducted to the Pinball Expo Hall of Fame, the Guinness World Record holder for the longest-running pinball event. Schmidt was recognized for his sonic contributions to some 45 classic pinball titles, both as a composer of music and sound effects, as well as for inventing technology that advanced the early field of game audio. The award is just the latest notch in Schmidt’s expansive, accomplished career, one that has spanned major evolutions in game audio innovation and continues to this day.

A Cabinet Composer

Schmidt would eventually dive deep into the world of video game audio, but before the transition, he cut his teeth on those pinball cabinets at the Chicago factory.

“One of the coolest parts of working [at Williams] was the pinball production floor,” Schmidt says. “There’s literally 350 human beings on an assembly line with soldering irons and electric drills and screwdrivers putting the things together, wiring them and putting the lights and the ramps on the playfield. My office was right next to it, so I could literally stand at the top of the stairs and see the whole factory floor.”

The first pinball title for which Schmidt composed all the music and sound effects by himself was Space Station, an astronaut-themed machine designed by a programmer who would go on to become one of Schmidt’s lifelong friends, Ed Boon.

“If you look up his name,” Schmidt says, “you’ll find he went on to become the creator of Mortal Kombat.”

A year later, Schmidt worked on his first video game for Williams, 1988’s controversial, ultra-violent NARC. The photorealistic run-and-gun arcade game put players in control of Max Force and Hit Man, two super-powered D.E.A. agents. Armed with a high-powered arsenal, players busted waves of drug dealers to face final boss Mr. Big, a surreal criminal kingpin rendered as a giant, grotesque head mounted on a hovering platform.

Schmidt’s chugging, snare-driven theme for NARC would eventually inspire an unlikely cover version by the Pixies — a track that originally appeared as a B-side on the 1991 single for “Planet of Sound.”

“I had left Williams to start freelancing and had a party,” Schmidt says, recalling the first time he heard the cover tune. Schmidt’s friend Eugene Jarvis, the developer of classic arcade games like Defender and Robotron, had arrived with an unexpected gift in the form of a CD. “[He] said, ‘I think you might be interested in this.’ Apparently, Williams had been contacted by the Pixies saying they wanted to cover the NARC theme, but they deliberately wanted to keep it a secret until the CD was out. I had my little MIDI version, but their full-on band version was really cool.”

Chipping In

At the time, Yamaha’s FM synthesis chip was the primary driver behind game audio, converting mathematical algorithms into synthetic sounds. The technology was an ’80s staple, but by the end of the decade, Schmidt wanted to push the possibilities forward, so he took it upon himself to do just that. In 1989, Schmidt invented the BSMT2000 (short for Brian Schmidt’s Mouse Trap), a new arcade/pinball sound chip capable of waveform playback that made its debut in the 1991 Batman pinball machine. The chip enabled game composers to use samples of real instruments and recordings, albeit incredibly short ones — a major influence on the staccato, frenetic energy of early game music.

“Memory has been the driving factor in game audio for a long time,” Schmidt says. “The prototypical ’90s arcade game sound was using something called sample playback technology. Because the memory we had was so limited, the sounds we used had to be short, and we couldn’t really have a big variety of them.”

To compose for the chips, Schmidt would first write the score longhand on staff paper. Once he had that figured out, he would then convert the score into something called a note list, “a list of instructions for what note to play, how long to play it, what timbre, whether or not there should there be a little pitch bend, etc.” Schmidt says. “We’d literally do that in a text editor. Then we wrote a little operating system that would parse these note lists and send commands to the chip at the right times to play the note.”

Schmidt thrived under the technological constraints, and spent the next nine years of his career freelancing on video games like Mutant League Football, the Super Nintendo-era Madden series, Desert Strike, and countless others for companies like EA, Sega, Capcom, and Namco.

In 1998, Schmidt moved his family from Chicago to Seattle to work on game audio technology at Microsoft, where he soon joined the fledgling Xbox team. The year the Xbox debuted, 2001, marked a major shift in game audio.

“In 2001, everything changed, because the PlayStation 2 and the Xbox shipped games on DVD,” Schmidt says. “All of a sudden, you had the memory to do these big orchestral scores.”

While Schmidt had a heavy hand in expanding the sonic capabilities for video games at Microsoft, one of his most recognizable contributions to the console took him right back to the strict constraints of the late ’80s.

Near the end of the console’s development cycle, Schmidt was assigned to write the Xbox startup sound on an incredibly tight deadline. Even though Microsoft only needed eight seconds of audio to match the startup animation, the project might have appeared impossible to other composers.

“The ROM chip on the motherboard of the Xbox that contained the startup kernel was only 256 KB. By the time you factor in the kernel and some of the startup animation visuals, there’s only about 28 KB left for the audio. If you do the math, if I want a wave file that’s eight seconds long, 28 KB isn’t even one second of 8-bit mono audio,” Schmidt says.

Undaunted, Schmidt found a solution by recoding the audio system he’d written for pinball and arcade games and porting it to the Xbox, composing the startup sound using the same note-list technique he’d been using a decade before. The mad scientist startup sound he ended up with, now synonymous with the classic console, barely went through any oversight from Microsoft. “The window we had was so short we just did two or three takes of it before it was finalized,” Schmidt says.

Game Audio Levels Up

That same year, Schmidt and a coalition of nine other game composers won a major victory for the industry. Since 1999, at the behest of game composer Chance Thomas, the coalition had been lobbying the National Academy for Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS), the group that organizes the Grammys, to make video game soundtracks eligible for the award.

“This was just about the time that the transition is starting to happen between MIDI-generated music and actually being able to record something in video game music,” Schmidt says. “Essentially, our job was to educate NARAS that video games have music now that’s worthwhile of consideration for the Grammys.”

In 2001, they won their case – NARAS changed the “Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or For Television” to “Best Soundtrack Album for Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media,” opening the door to game soundtracks. Thanks to the coalition’s work, Journey went on in 2012 to become the first video game soundtrack to earn a Grammy nomination in a renamed version of the category, “Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media.”

Even though Schmidt had helped open up the traditional media world for game composers through the Grammys, eight years later in 2009, he realized he needed to do the opposite – open up the game audio world for folks more versed in film, music, and television composition.

“Because we didn’t have the memory constraints anymore, the industry was starting to go towards more traditional TV composers and film composers who didn’t have a background necessarily in games,” Schmidt says. “And so as these other composers are coming in from more traditional media, I noticed they were tripping over the same few issues, because games are a very different medium than film or television — one these composers and sound designers didn’t quite get yet.”

The annual GameSoundCon, which wrapped up its latest edition in early November, was Schmidt’s attempt to bring all those new game composers with traditional backgrounds together in one place, and help to fill in the gaps by hosting industry workshops and speakers.

“I wanted to help teach composers what techniques we have evolved to map this inherently linear medium, music, onto this inherently non-linear medium, video games,” Schmidt says. “So it was teaching them some of those techniques, how game engines work, how does surround sound work in games, what are some of the technical constraints.”

After five-and-a-half years of teaching for DigiPen’s music and sound design program, a program whose initial development he contributed to, Schmidt says he sees a lot of parallels between the college’s culture and the culture that initially landed him his own first break into the industry.

“Of the people tangentially involved in the computer music studio at Northwestern, one of them worked at this pinball company in Chicago called Williams Electronic Games, and there was a job opening,” Schmidt says. “This speaks to a place like DigiPen, where… you’re creating these networks that become professional networks when people go out into the real world and get jobs — jobs that lead to other jobs.”

Jobs that, maybe, lead to career-defining achievements like the Pinball hall of fame.