Jazno Francoeur, director of the BFA in Digital Art and Animation program, insists there isn’t a clandestine Disney conspiracy happening here at DigiPen.

“It’s not like there’s this secret Disney cabal,” he says with a laugh. Though, later on in conversation, he does concede, “After a while, some of us did start jokingly calling it ‘Disney Pen.’”

He’s referring, of course, to the large contingency of former Disney artists and animators who roam the halls of DigiPen on a daily basis. DigiPen’s BFA faculty is indeed stacked with a number of people — nine to be exact — who previously worked on Walt Disney feature films.

They’re no strangers to one another either. Many of them have known each other since they graduated college and have worked together, both as animators and educators, for decades. How did they all end up at DigiPen? While their paths have veered in slightly different directions on their journey here to Redmond, the majority of them share a similar story. And it all begins with what professor Richard Morgan calls “art school on steroids.”

Part I

Dreams and Desk Naps

When The Little Mermaid splashed into theaters in 1989, the film’s success marked the beginning of what’s now referred to as the “Disney Renaissance.” The aquatic adventure ended a long drought for Disney Animation, which according to Francoeur had not released a major hit for quite some time.

“I remember going to the theaters to see The Black Cauldron and being pretty disappointed, feeling like Disney Animation had kind of dropped the ball,” he says.

Francoeur wasn’t alone in his assessment. The widely-panned 1985 fantasy marked a low point in Disney’s slow but steady descent in critical and commercial success since the early ’70s. Bringing in just half its production budget at the box office, The Black Cauldron nearly bankrupted Walt Disney Feature Animation.

The Little Mermaid, however, turned things around. Its biggest critical and box office hit since 1977’s The Rescuers, the film re-established Disney’s faith (as well as its audiences’) in its animated productions. Revitalized by the success, Walt Disney Feature Animation decided to expand beyond its Burbank, California, headquarters that same year, opening a brand new production studio in the also new Disney-MGM Studios Theme Park, just outside of Orlando, Florida. To staff the new studio, Disney kicked off what Francoeur calls “a hiring blitz,” actively recruiting at select art schools across the country and funneling qualified college artists into its intensive Florida internship program to gauge their potential. That internship is where most of the DigiPen animation faculty began their own journey at Disney.

For some, the path there was fairly straightforward. Professors Richard Morgan and Pamela Mathues, for instance, had known they wanted to be Disney animators since they were children.

“When the Fantasia re-release came out, I just got hooked,” Mathues says. “I would always draw the Fantasia characters.”

For a 12-year-old Morgan, it was the emotional power of a scene from The Rescuers that decided it. “I knew these were just drawings,” Morgan says, “but to make someone feel something so strongly with just drawings … I had to be a part of that.” When Disney recruiters came to Morgan and Mathues’ campuses, they leapt at the opportunity and applied for the internship. After submitting their portfolios of figure, gesture, and animal drawings, they made the cut on the first try.

So there I was, the sweaty security guy showing up at the drawing class.”

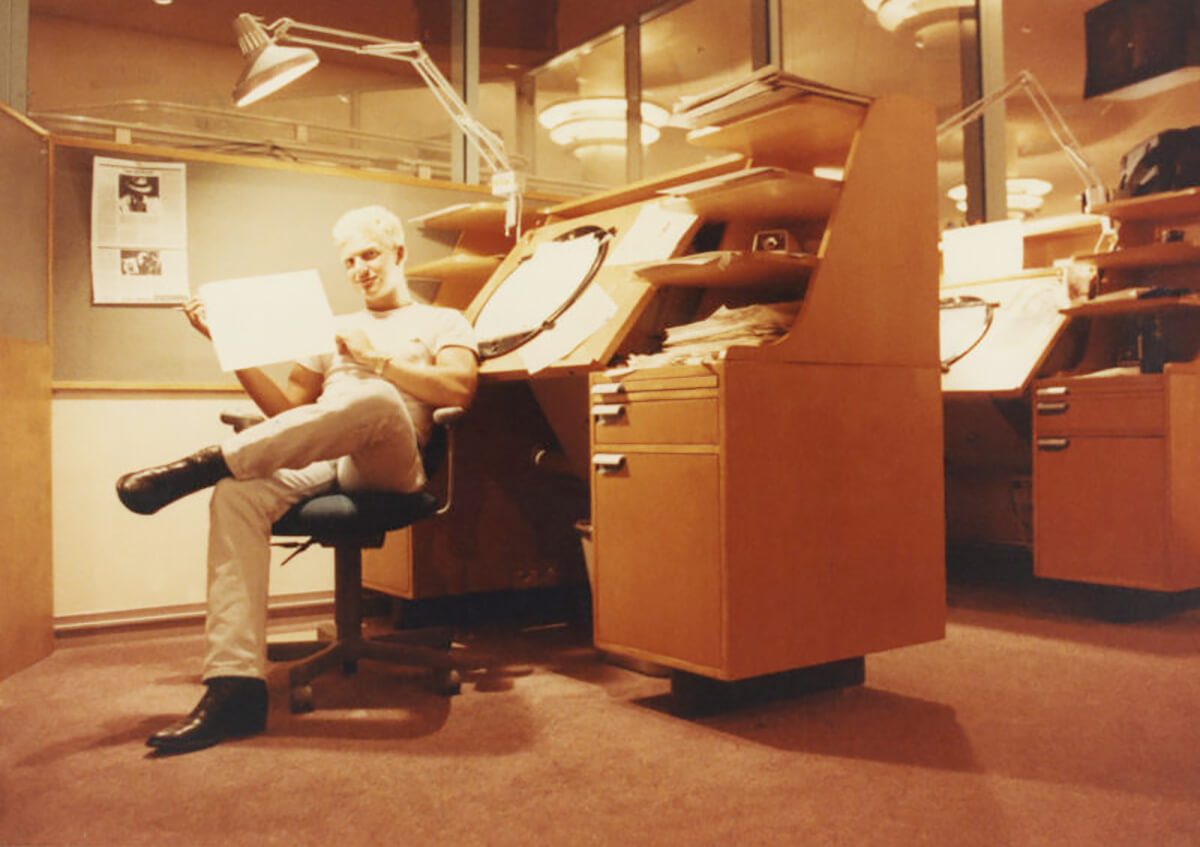

For Francoeur, who was studying to illustrate kids’ books, animation as a vocation had never occurred to him before Disney showed up at his college campus.

“My dad said, ‘You know, son, you need to pay off those loans, so if I were you I’d go to that presentation.’ And I said, ‘Dad, I don’t know anything about animation,’” Francoeur remembers.

Despite his own misgivings, Francoeur met with the recruiter, applied for the internship, and was rejected.

“I think it was the rejection that really inspired me,” Francoeur recalls, saying he was suddenly possessed with an all-encompassing desire to work for Disney. He immediately began buffing up the skills that needed improvement, and he successfully landed an internship when the Disney recruiters came back the next year.

For professor Antony De Fato, the path to the Disney internship was more obtuse. Rather than Disney coming to him, De Fato went to Disney. “I’d always wanted to do animation and work at Disney,” De Fato says, “but when I went to L.A. and submitted my portfolio, they said I wasn’t good enough. In fact, pretty much every place I submitted portfolios to told me to do something else with my life.”

After the rejection, De Fato got a job as a security guard for a company that, by strange coincidence, counted Disney among its clients. “Six months after I started, by pure, dumb, stupid luck, Disney decided they wanted their security to be in-house, so I interviewed again, this time with Disney directly instead of the guard company, and got hired.”

With the permission of his boss, De Fato was allowed to attend Disney’s drawing classes taught by some of its veteran animators. De Fato worked the graveyard guard shift though, so attending those lunchtime classes made for some strange sleeping arrangements.

“Since I got off at 7:30 in the morning, I’d just go to the parking lot and sleep in my car until noon. It was a small two-seater Honda CRX I crammed in, and it’s L.A. in the middle of the summer,” he says. “So there I was, the sweaty security guy showing up at the drawing class.”

De Fato’s dedication paid off. His drawing improved and impressed enough people to land him an internship in Florida. That wouldn’t be the end of the unusual sleeping arrangements though. If anything, once the internship began, it became the norm.

“The internship was so grueling that we were literally sleeping under our desks in sleeping bags,” Morgan says.

“I have to say, that was boot camp,” Francoeur remembers. “It was the most difficult thing I have ever done. I fell asleep many nights with a pencil in my hand.”

Sleeping under desks and sweating — this time due to anxiety rather than heat — was the norm during the three-month Florida internship program. Much of that anxiety stemmed from the fact that, for the majority of the recruits, their collegiate art school experience was in drawing, and drawing alone.

“I wasn’t coming from an animation program. I could draw but I couldn’t animate,” Francoeur says. “I didn’t even know what squash and stretch was.”

To make up for it, the interns stayed far beyond the required 40 hours per week, often working seven days a week on the assignments they were given in order to impress Disney. “It was non-stop,” Morgan says, “as much as you could possibly work.”

“It was interesting in that it was a whole bunch of people dealing with imposter syndrome,” Mathues says, a sentiment her DigiPen peers all echo almost verbatim. “When you’ve put Disney on a pedestal for so long, to actually be there doing it is just … kind of unreal. It’s like, ‘They must have gotten my portfolio mixed up with someone else’s. Why would they let me in here?’”

The internship’s scope increased gradually — beginning first with general assignments, then a series of two-week stints within the various animation departments to get a taste of each — all before the final test.

“[Then] they start easing you out onto the production floor, which is scary,” Francoeur says.

The work interns did on those larger Disney productions was still small — what De Fato calls “boogermation.”

“They were tiny little drawings the size of a booger,” De Fato says. “Just miscellaneous people in the backgrounds of scenes. The idea was, ‘Hey, you can’t screw this up too bad because they’re only yea big.’”

Part II

Renaissance Family

“We got lucky,” Francoeur says, “We hit this wave just as it started cresting.”

When the intern crew was officially hired, many of the young upstart animators suddenly found themselves working on The Lion King, the highest-grossing animated film of all time upon its release, and the first in a string of animated classics they would contribute to in the decade-long Disney Renaissance.

For a moment, the intense lingering imposter syndrome remained.

“It was pretty gut-wrenching once you actually started the job and were thrown into this team and everyone is doing 8-12 plus drawings a day,” Morgan says. “Then you’re over in the corner going, ‘Oh, neat. I got two drawings done today.’ And then, the breakdown artist checks them out and goes, ‘Well, you messed up almost everything on those two, so you might as well start over.’”

The high bar Disney set for quality meant the working culture in the studio was one of constant checks, a culture the unsure upstarts took time getting used to.

“Every drawing you do gets checked by somebody,” De Fato says. “I never once did a drawing that was right the first time in the 10 years I was at Disney. You start out and they’re marking all your drawings up in red, and you’re like, ‘Oh my god, I’m failing horribly!’ But once you realize that’s just a part of the process for everyone, you finally relaxed.”

Indeed, it was all a part of the process, the merits of which quickly became clear.

“One week of getting my drawings checked at Disney and the quality shot up more than in the six years I spent on my own trying to improve,” De Fato says.

You’d be picking your nose and suddenly you hear tapping on the glass, and you look up and there’s a family videotaping you.”

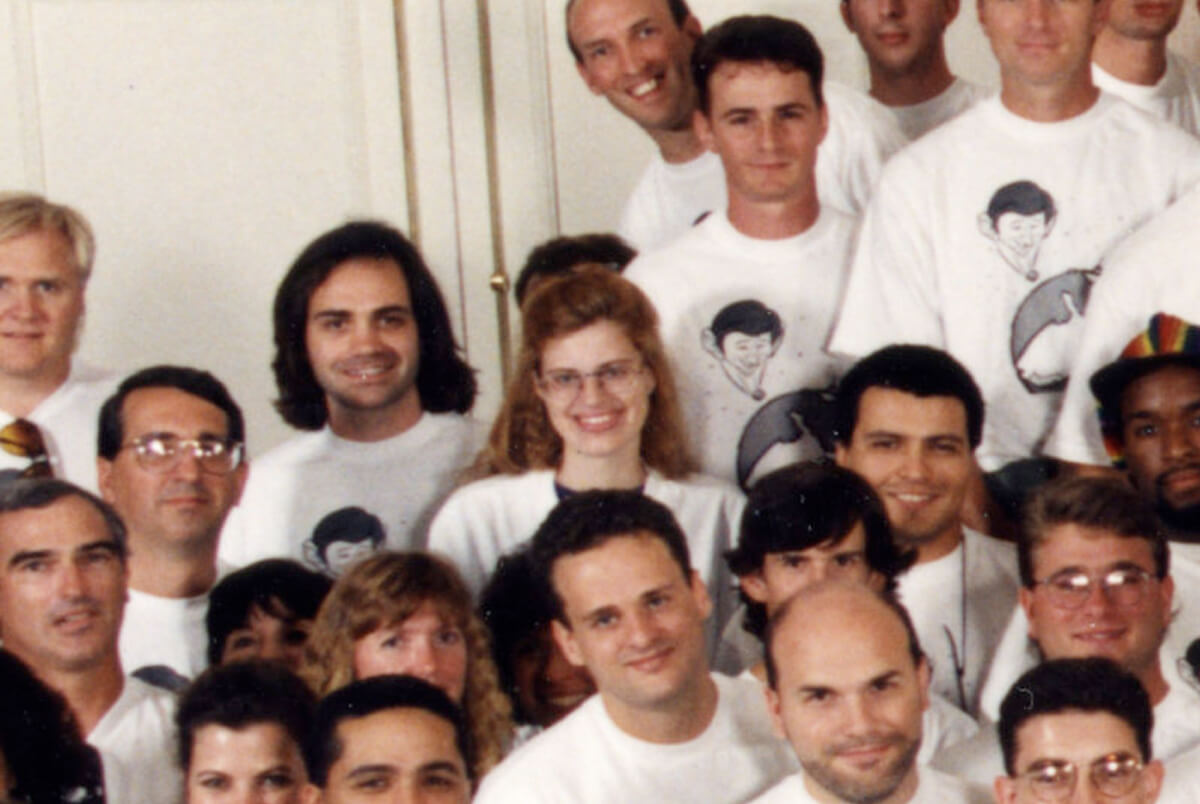

The other thing that softened the initial shock was the fact that everyone happened to be going through the same thing, and they were all generally the same age. People bonded quickly and held each other up when production got intense.

“Something that was unique about the Florida studio is we all went through that same internship program,” Mathues says. “And because of that we were all like a family. It was supportive in that way.”

When animators weren’t heads-down working on scenes, they were sometimes prank calling each other on their desk phones, drawing caricatures of each other, or in some cases messing with the tourists at the Disney-MGM Studios Theme Park. Since the studio was located inside the park, rookie Disney animators were literally put on display for park goers — their desks pushed up against glass for families to gawk at and admire.

“Like a zoo animal,” Francoeur laughs. “You’d be picking your nose and suddenly you hear tapping on the glass, and you look up and there’s a family videotaping you.”

The unusual set up was jarring at times and led to some strange encounters.

“[One time] this little 5-year-old kid got up on the railing, banged on the glass, slipped, and got his head caught in between the railing and the glass for five hours until they brought a welder out to dislodge him,” Francoeur says. “I felt so sorry for that kid.”

Those encounters went both ways, however.

“We cut these ping-pong ball things in half and would stick on googly eyes and draw on them, and put them in our eye sockets,” Mathues says. “Then when families would come down the corridor we’d suddenly look up at them and they’d freak out.”

After Pocahontas, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Hercules, the Orlando studio was given its first shot at producing a film entirely independent of the Burbank studio. The result, Mulan, is unanimously considered by the DigiPen crew as one of their favorite projects.

“I would say it’s probably my favorite for the same reasons it was the hardest,” Mathues says. “I was [working] on the main character, and since Mulan is in almost every single shot, I basically just lived at the studio. I would do whatever it took to make it look good.”

Francoeur, who by that point had become a specialized visual effects animator, remembers one particularly complicated scene that consumed his time: cherry blossoms gently blowing in the wind onto Mulan’s father’s lap.

“We finally show it on a Sunday because we’re working seven days a week, and the director approved it,” Francoeur recalls. “But the chair of the department came in and unapproved it. He said, ‘I think your blossoms look like nipples. I need you to reanimate it.’ I remember it was 3 a.m., and our crew is looking at each other — like, ‘This is crazy, this is nuts.’”

By the end, it was all worth it. The film released to critical success, many reviews particularly highlighting the Florida studio’s beautiful animation.

“It was sort of like when you got done with it you felt like you’d been in a war with your band of brothers, and you’d gone through so many things together and you’d succeeded and come out victorious,” Mathues says. “We were really proud of the kind of work we’d done … and just that we’d survived it.”

Part III

From Disney to DigiPen

After the release of the second and third Orlando-produced films, Lilo & Stitch and Brother Bear, animators at the studio started seeing “the writing on the wall,” as Mathues puts it.

“They started doing things like cutting our pay,” Mathues says, “and then they brought in this guy who’s a classic closer. He’d go studio to studio, and about a year after he arrived, they’d shut down.”

First came a wave of firings at Disney’s California studio, then Disney’s Paris studio closed. Then the “closer” showed up at Disney Orlando.

“I actually started shipping my stuff home from the office,” Francoeur says. “I knew in my heart what was coming, but I still wanted to stick it out until the bitter end.”

Eventually, the Florida studio shut down as well, leaving nearly 260 artists without jobs in January of 2004. It was the same year Disney would release its last 2D film in theaters for the next five years, Home on the Range.

“The team working on that movie started calling it ‘Apocalypse Cow,’ because it was so bad,” Francoeur says. “The story was Roseanne Barr as a cow who lost her farm, which just isn’t funny, and everyone in the room working on it just said, ‘This is awful.’”

At the same time, Disney’s Australia studio began pumping out low-budget direct-to-video sequels of the company’s 2D franchises while Disney corporate ownership transitioned its larger animation budgets to 3D production.

“They saw the 3D movies making money and the 2D films making less money,” De Fato says, “and they figured, ‘Oh, it’s because everyone wants to see digital!’ But the reality was Pixar just had better stories. The way I think about it is: Sculpture doesn’t replace painting — they’re different mediums. It’s [about] what kind of story do you want to tell, and how do you want to tell it?”

The crew would go their separate ways — some spending time river guiding, woodworking, plein air painting, or traveling Europe. Later that year, Francoeur came to a crossroads. He could either take a job working on Richard Linklater’s rotoscope-animated film A Scanner Darkly, or he could head to Redmond, Washington, to teach the very first cohort in DigiPen’s fledgling BFA in Digital Arts and Animation program.

Francoeur was just the first Disney veteran to join the team. As DigiPen began rapidly expanding, not only in enrollment but also with new international campuses in Singapore and Spain, what was once a boutique animation program suddenly became much bigger.

“It’s hard to find someone who can do all the things this job demands,” Francoeur says. Whenever DigiPen needed to hire new animation faculty for the expanding program, Francoeur turned to the few people he knew were capable — his former Disney colleagues. “It was kind of just this never-ending thing,” Francoeur says.

Eventually, DigiPen recruited the likes of Dan Daly, Antony De Fato, Peter Moherle, Pamela Mathues, Richard Morgan, Chris Poplin, Travis Blaise, and longtime Pixar technical director Mark Henne, as well as Geraldine Kovats and Woody Woodman, who each spent five years teaching at DigiPen. Some of those instructors, such as Francoeur, even spent time teaching at both the Redmond and Singapore campuses over the years.

Whenever I have a student, I’m really committed to giving them as much support as I possibly can, so they get over that familiar imposter syndrome.”

As proud as Francoeur is of his accomplishments at Disney, according to him, working at DigiPen has brought him even greater joy.

“Building this program up from the ground floor and watching it grow around the world has been so exciting,” Francoeur says. “At Disney, I was at a desk all day expending energy. At DigiPen it’s the opposite — I’m up in front of a class every day getting energized by these students.”

The lessons Disney taught its former employees, as well as all the trials and tribulations that came with it, are never far from the instructors’ minds.

“Whenever I have a student,” Mathues says, “I’m really committed to giving them as much support as I possibly can, so they get over that familiar imposter syndrome and the ‘I’m not good enough’ … to where they absolutely should be. I’m so grateful that I’ve been able to help students get to that point and get them into places where they really have a shot at doing something and making a big difference in the animation industry.”