Mere days remained before the official unveiling of Drakan: The Ancients’ Gates at E3 2001. Brigitte Samson, an animator at Surreal Software at the time, was among the developers working frantically to give the dragon-riding PlayStation 2 game a proper reveal at the world-renowned gaming convention. “It runs at five frames per second, it’s a slideshow! E3 is in a few days, we have to make it work!” a concerned Samson remembers saying as the deadline crept closer. Whether it was the number of skeletal bones in a character mesh or shaders used in a level, something had to be fixed.

“It was a real challenge because you have to announce the product with a trailer, but you still need to show gameplay and stay genuine about what is going to be delivered,” says Samson. As demanding as that moment was, Samson’s experience on multidisciplinary teams in the fast-paced game industry still helps her today in her work guiding students as a senior lecturer in DigiPen’s Department of Digital Arts.

Drakan’s big reveal at E3 2001 was a success. Players were enamored with the impressive visual effects of the fantasy world, especially the next-gen character modeling on the game’s protagonist, Rynn. Journalists and convention-goers also took a liking to Rynn’s trusty dragon, Arohk, specifically calling out its lifelike idle animations.

“In the game you dismount your dragon and you go off and do your thing. The dragon is left by itself until you return, so I took the time to create idle animations for it,” says Samson. At first, not everyone on her team saw the value in spending extra time on Arohk. “They were asking me why we needed more idles, why add more animations. But he was an animal! He is going to do stuff while he is waiting.”

Developers often misunderstand each other’s design choices when communication isn’t strong, something Samson tries to drive home to her students on junior-level game teams. Early in pre-production, Samson says students tend to silo into their own bubbles. But with guidance and time, team members learn to talk to one another, creating a much more effective dynamic. “It’s really fascinating to see the skills students bring to collaborate towards a common goal,” says Samson. “Some teams click, other teams have a harder time. But that’s why students come to Seattle and to DigiPen, to get the experience of multidisciplinary collaboration, in addition to building their specific discipline skills.”

Despite the impending deadline, Samson finished Arohk’s idle animations just before the big show. “When my team came back from E3, they mentioned how entranced people were by the life that the dragon had, saying things like ‘Did you see the dragon scratch his ear?’ or, ‘He’s alive!’” Samson says. Even though she wasn’t at the show to get direct feedback on the creative animations, she still felt a powerful sense of recognition. “The product is about moving the audience. That’s the goal.”

When teaching, Samson pushes students to find ways to impress players by working closely with team members outside their discipline. She often cites working with different designers and uses one particularly menacing enemy as an example. “In Drakan, there’s a big yeti named Daemog with a freezing breath attack that a lot of people talked about,” says Samson. “The first time you see Daemog is when it’s coming out of its cave, and I worked with the level designer to animate within that arena space to help make it a memorable moment. Daemog also had loud roar, and I worked with the sound designer to determine how long each animation should last and how to distinguish it from other attacks.”

Working together can have a big impact on the player, but it also helps creators feel proud of their work. “Daemog became my little baby,” says Samson. “He’s a gruesome monster that picks up and chews your character. It’s weird how you connect with a character once you start to animate it.”

One of the benefits of working on multidisciplinary teams are the unexpected solutions students find to their problems, something Samson has experienced firsthand. During the development of Drakan, one programmer working with the game’s early 3D AI navigation faced an issue where hordes of enemy orcs had trouble avoiding running into walls and other enemies. “I was responsible for the attacks of the dragon, including a fire-breathing attack,” says Samson. “The dragon can set the orcs on fire, and I convinced the programmer to keep some of the weird imperfections of the AI’s movements. I added an animation where they would raise their arms in a total panic, and we got a kick out of how believable it looked!”

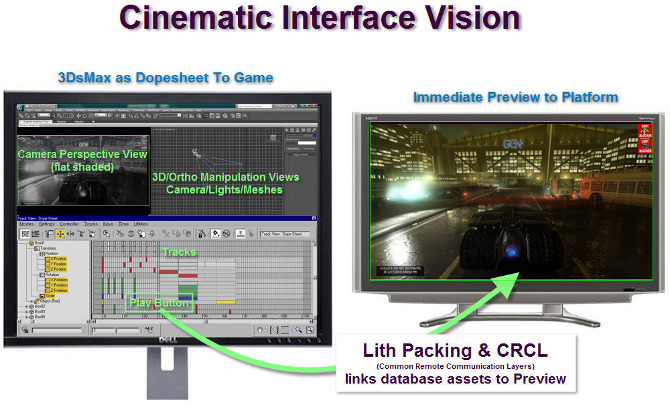

Teamwork was a crucial part of Samson’s experience working on Drakan, and it remained a throughline of her varied career. While working on Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor and its enemy-ranking Nemesis System over a decade later, she initiated the development of tools to create cutscenes where the camera would pull back during gameplay, introducing visual effects and unique lighting for each camera cut. For a game this expansive, the team worked on cinematic moments within multiple systems and programs. “The workflow to create cutscenes was too long,” says Samson. “The amount of cutscenes we envisioned was not sustainable, so I worked with the lead tools programmer to combine existing and new plug-ins to establish a new creation workflow that would benefit everyone.”

With Samson’s new tool, work on a typical cutscene went from one week to an average of three hours. “Assembling all of what it takes to create a cinematic moment was a bit overlooked,” Samson says. To remedy this, the new workflow gave artists, level designers, animators, and a variety of other creators the ability to iterate and immediately preview their cutscenes in-engine with the click of a button. “The tool was agile and light enough that other designers saw how they could push the system further. It allowed us to engage with players through cinematic moments in a way that was more immersive from other games at the time.”

DigiPen student game teams also benefit from cross-functional work among different roles, a process that Samson believes provides a vital confidence boost and better game creation. “Students are brought to think outside their own discipline,” Samson says. “It expands their world and their ability to communicate. For example, artists learn to communicate with programmers and designers, and this helps artists and other team members elaborate and understand the look and feel of the game.”

Ultimately, Samson says she hopes her experiences help her students see the many different areas they can make a positive impact during development. “I always find it really exciting to bring student artists into a game team,” says Samson. “I want them to understand there are so many ways for them to contribute to a team, and that the capacity to create a collaborative environment is key for successful projects.”