Knuckle Knockout plunges two to four players into an all-out brawl, scrambling around 2D battle arenas and hurling haymakers with “extendo fists” in a fight to win three melee combat rounds. The sophomore action party game, developed by DigiPen student team Royal Court, is notable not just because it’s a whole lot of fun, but because it was developed to be fun for everyone.

Going above and beyond expectations for sophomore game projects, Royal Court included a suite of accessibility features like a colorblind-friendly palette, a font option for dyslexic players, and a toggle to reduce screen shaking for motion sickness. “Since I started at DigiPen, I’ve heard a lot from professors in class, and even from friends, that accessibility in games is really important,” says BA in Game Design junior and Royal Court design lead Jean Pate. “So when we started on this project, I just thought, ‘OK, let’s do it!’”

Knuckle Knockout began its life in project course GAM 200 as a completely different game named Demo Dan, a tower-ascending action platformer with floors of enemies that players take out using environmental hazards. “We made this extendo fist mechanic for it where the player clicks in a direction, and the fist pushes the player around while damaging enemies,” says BA in Game Design junior and Royal Court producer, user experience, user research, and level designer Teddy Delaney. “Our program director, Jeremy Holcomb, walked by and went, ‘You know what? You guys should make a fighting game using that mechanic!’ We thought it was kind of crazy, but as soon as we added a second controller, it felt real and it felt fun.”

While turning their project into a multiplayer fighting game felt unusual at first, adding accessibility features to Knuckle Knockout came naturally to Royal Court — in part because a number of the team members themselves stood to benefit from them.

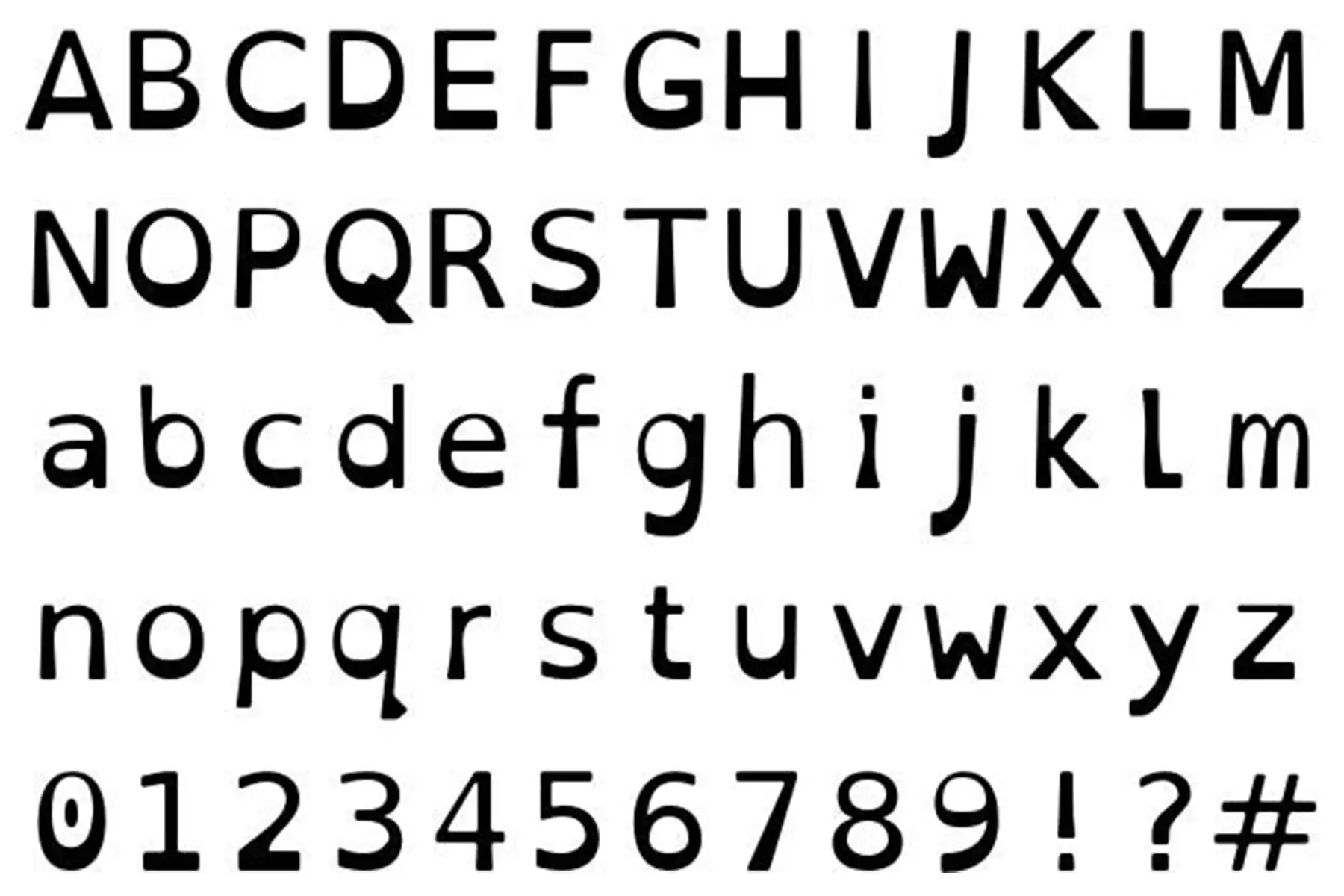

“In high school, I realized that I’m undiagnosed dyslexic. I have to read everything five times to understand it. It’s all a jumble,” Delaney says. He found what he dubs “a magic solution” in the OpenDyslexic font, a free typeface that gives similarly shaped letters like “a” and “q” more distinct forms, adding bolded weight to the bottom of every letter and tapering to a thinner top. “Your eye is able to draw an imaginary line under each letter, so you’re not flipping words and letters don’t shift around,” Delaney says. “There aren’t a lot of dyslexic-friendly features in games, and I think they should be more prevalent.”

Delaney pitched the ability to switch between the game’s default font and OpenDyslexic to the rest of Royal Court — an idea that was warmly embraced. Implementing the font took some careful thought and intentional design choices. “In order to be able to swap the fonts out, we couldn’t have text baked into images, so everything had to be a text object,” Pate explains. “If it’s not baked in, you have to make it so that the width of the screen elements can accommodate both font sizes, which is much easier if you do it up front.”

Royal Court’s default font in Knuckle Knockout was chosen because it played well stylistically with the rest of the game, but OpenDyslexic’s unusual type form meant having to make larger design choices to accommodate it as well. “From a UX perspective, it was interesting creating the UI and menus and making sure that OpenDyslexic felt good in them too,” Delaney says. “We had to make sure the style was universal enough to accommodate a font with such specific, untraditional characteristics.”

Incorporating OpenDyslexic started an accessibility feature “domino effect” on the team, which continued when BS in Computer Science in Real-Time Interactive Simulation junior and Royal Court technical director Aditya Prakesh mentioned he was colorblind. “When we started creating colors for our characters and levels, we were trying to think about how to make it so players wouldn’t be confused about who they’re playing at any given time,” Delaney says. “We never wanted that to be a point of confusion.”

The team started diving into color theory, exploring which parts of the color spectrum were most opposite from one another. “I worked with our programmer Matt [Zearing], adjusting the colors to make sure there was contrast where there should be and there wasn’t contrast where there shouldn’t be. We added stripes and zig-zags to some of the character outfits to help differentiate them,” Pate says. In addition to running the color palettes by Prakesh, the team also ran screenshots of their palettes through filters that simulated what they looked like to people with each of the eight different types of colorblindness. “That way we made sure everything was still distinguishable and worked for all different kinds of colorblind players,” Delaney says.

Implementing features to make your game more accessible is also really good for your UX in general.

Further into development, Pate noticed that Knuckle Knockout’s shaking effect, a visual enhancement meant to accentuate the brawl-like action on screen, started to make her feel ill. “Sometimes when I play games I get motion sickness, and at one point in development it was just too much for me,” Pate says. As a simple solution, the team added a motion sickness toggle that turns off screen shaking for players. “Implementing features to make your game more accessible is also really good for your UX in general, because an experience that’s better for someone with a disability is also generally better for people without a disability,” Pate says.

Delaney and Pate say that in addition to making games better for players of all kinds, adding accessibility features can make you a better developer too. “Planning ahead makes things much easier later down the line. I’m glad we started creating the game with accessibility in mind because it would have been much more difficult to go back at the end and fix things,” Pate says. “It’s easy to feel accessibility is this big obstacle and put it off until the end, but it doesn’t have to be a big thing! There are a lot of small improvements you can make that don’t cost that much time, and they really add up to a lot later on.”

Now that he can quickly keep track of his health during gameplay, easily read the damage he’s dealt, and effortlessly navigate the game’s menus, Delaney echoes the sentiment: “It’s really a small price to pay so more people can play!”