Chess, one of the oldest continually played games in the world, has changed very little since its invention in the sixth century. Blame it on poor developer support or simply a lack of vision, but chess fans have been left starved for any new content or updates for the better part of 1,500 years. Fortunately, three DigiPen BS in Computer Science in Real-Time Interactive Simulation students have finally answered the call, forever changing chess history with one simple, but crucial, twist on the formula: They added guns.

The result, FPS Chess, shot to the number one spot on Steam’s New & Trending chart just days after its release, racking up hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube and launching viral memes on social media celebrating the long-awaited advent of “CHESS 2.” “To be honest, I really had no idea it would be nearly as successful as it was,” developer Hadi Alhussieni says.

Before FPS Chess, Alhussieni and fellow developers Yi Qian and Chau Nguyen had collaborated on game team projects both big and small throughout their DigiPen student career. Their prior games included the 2D chicken platformer Fowl Magic, the side-scrolling dark fantasy Sightbringer, and the physics-based 3D adventure Grav-Link. Come senior year, the three decided to collaborate for their final game as team Meta Fork, circling back to a “random idea” Alhussieni had filed away in a list of pitches as a sophomore.

“Chau and I really wanted to work on an FPS of some kind, and I just tied it together with the first thing that came to my head, chess, to make it unique. I kept it written in my phone for the next two years,” Alhussieni says. “Senior year was my last chance to try something crazy and ambitious, so I took the weirdest feasible idea in my phone and brought it to my friends.”

That “weird” concept’s serious potential was quickly made apparent. “Hadi did a prototype for his idea, and I was sold after playing it,” Nguyen says. “I always said that this game is going to be a big hit.”

FPS Chess begins like any normal game of chess. Starting with an overview of the board, players strategically move their pieces following the typical rules as they try to take the enemy king. The game diverges dramatically from the classic, however, when players attempt to capture an opponent’s piece. Everything suddenly shifts to an FPS view as the two pieces enter a live one-on-one deathmatch, complete with an instant replay “Kill Cam.” The winner of the duel keeps their piece, while the loser’s crumbles out of play, regardless of who was initially trying to capture who. “One of the most common questions we’d get is, ‘How much is your game FPS, and how much is chess?’” says Qian. “Our answer would unanimously be, ‘All FPS. You don’t need to know chess.’”

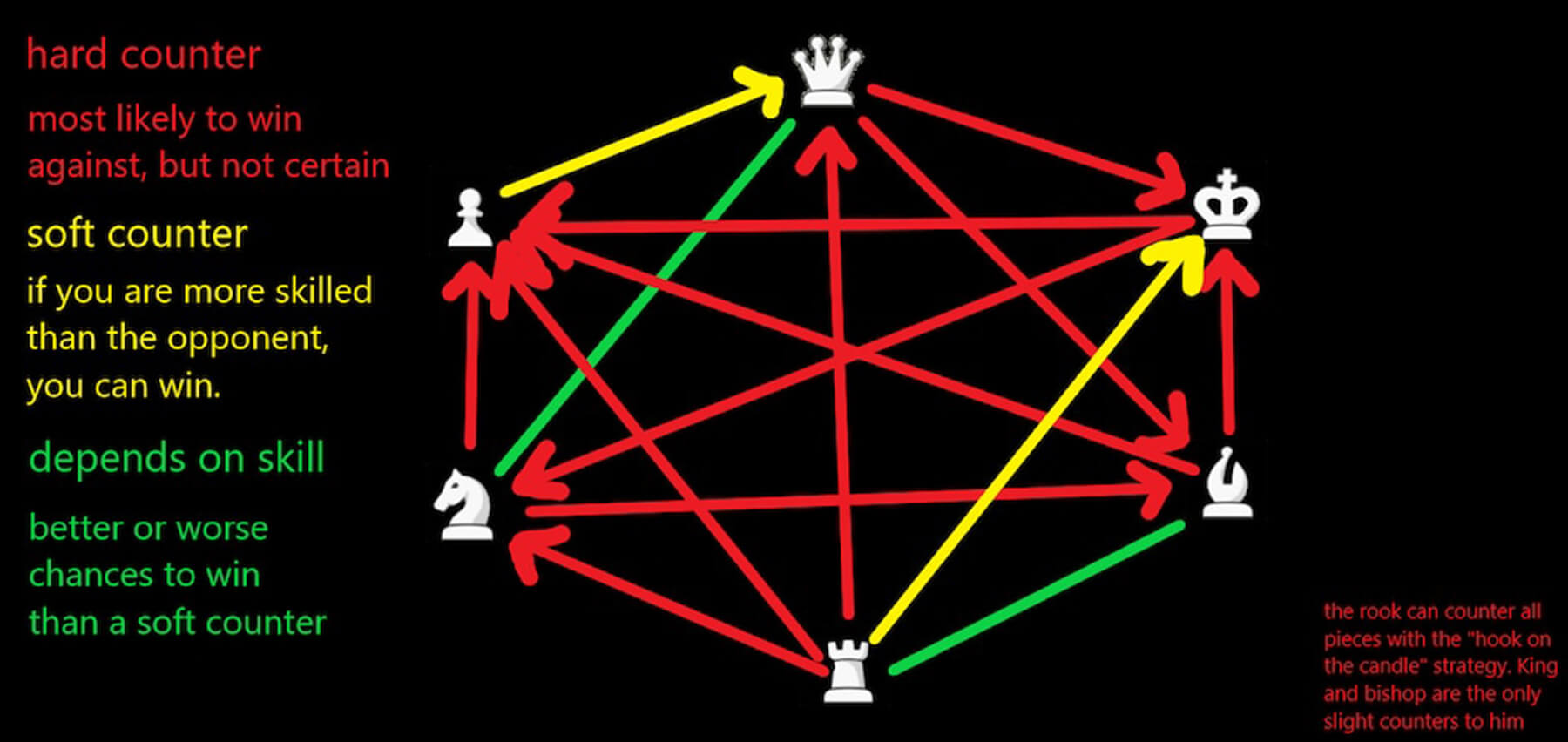

Even still, the turn-based chess element does add an interesting strategic dimension to the game that typical shooters lack. “The true purpose of chess in FPS Chess is to give control to the players to throw themselves into the matchups of their choice,” Alhussieni says. Choosing matchups is important, because much like the heroes from one of the game’s main inspirations, Overwatch, each piece has a completely unique toolkit with special weapons, abilities, and traversal styles that confer distinct combat advantages.

“For each piece I was definitely trying to think of abilities and weapons that would feel as if they fit,” Alhussieni says. The queen, being the most powerful piece in classic chess, naturally has the most intimidating loadout as well — a rapid-fire mini-gun, a brutal telekinetic grab and throw, and the ability to levitate. “We wanted to create this ‘psychic queen’ type of character that resembles Tatsumaki from [manga and anime] One-Punch Man,” Qian says.

On the flipside, lowly foot soldier pawns move slowly and wield a clunky musket, but their “strength in numbers” on the board lets them summon additional pawns to fight alongside them during battles. Crafting the combat abilities for FPS Chess proved an interesting design challenge: How do you create asymmetrical loadouts that reflect the unbalanced power between chess pieces, while still making any matchup feel winnable? “A pawn should feel like it can beat a queen if it plays well, but a queen shouldn’t feel like it was cheated by getting killed by a pawn,” Alhussieni says. “Weaker pieces must require more skill to succeed, and stronger pieces should be strong even with worse players.”

Another way the team leveled the playing field was by expanding the playing field. At first, deathmatches took place on the chessboard alone, with any space outside the board serving as mere window dressing. “I took a CG art class before senior year, so I had enough knowledge to model using Maya,” Nguyen says. When he joined the team, he brought his passion for graphics with him, creating a room with a fireplace, table, bookshelf, windows, chairs, and model train as a fun backdrop.

“It was weeks later when the room idea was coming together that I finally connected the dots and thought, ‘Wait … why are we worrying about making an interesting battlefield? Just jump off the chessboard and fight in the room!’” Alhussieni says. The decision immediately made combat much more dynamic, opening up interesting new gameplay strategies. Nguyen’s favorite piece, the rook, is able to grapple to high places like the bookshelf and take out enemies from afar with its sniper rifle. Alhussieni’s favorite, the bishop, is able to fly above sightline-reducing table and chair legs, dropping holy hand grenades on foes below. Qian’s favorite, the queen, is powerful in any situation, but opponents who know how to strategically use cover, like the model train that circles the room, can still gain the upper hand.

Meta Fork says their years of collaboration made much of the development on the game a breeze, but not everything was easy. Nailing the underlying networking that enables online and LAN matchmaking in FPS Chess was a huge hurdle. “At DigiPen, the professors really recommend you do not make a networked game without experience, and for good reason. It is a real challenge to learn how to make a good networked experience,” Alhussieni says. Despite that, Alhussieni’s fears that the game would only have two or three players at a time proved unfounded, as 230,000 people downloaded the game on Steam within its first few weeks on the platform, averaging 10,500 players a day. “Surprisingly, it was actually easy to find a lobby to play with after release!” Alhussieni says. In the four years since DigiPen began publishing student games on Steam, FPS Chess has quickly become the school’s most played and downloaded title on the platform.

Now that all three members of Meta Fork have graduated and found jobs in the industry, they’re enjoying the unexpected success their final student game has found online. But looking back, they say all four years of their time at DigiPen were vital to their own success. “The unique feature that makes DigiPen so different from any other regular CS university is the opportunity to work on game projects from freshman year,” Nguyen says. “My soft skills have developed dramatically over the years at DigiPen, I’ve become more confident in saying my ideas and feel more comfortable talking with new team members. DigiPen is also very different by teaching students low-level programming languages like C and C++, which is really helpful, because I’m the type of person that likes to dig around and see what’s really happening under the hood.”

Alhussieni says that even after graduating, he’s still been doing a lot of digging around under the hood of FPS Chess. Whether it’s optimizing the game’s GPU usage, exploring AI for a possible single-player mode, or continuing to balance the pieces’ combat abilities, it’s been hard to step away from the project. “I won’t be able to bring myself to stop working on FPS Chess in my free time as long as there are still people hungry for more content and improvements,” Alhussieni says. “It’s exhilarating to know that people are happy with things I made with my own hands — it makes me feel like I’m in the right line of work.”