DigiPen’s BA in Game Design program is built around six design concentrations — level design, narrative design, systems design, technical design, user experience design, and user research. Students spend their first two years learning about each design discipline, then choose two they would like to specialize in at the end of their sophomore year. While all six disciplines overlap and interact with one another, this series takes a closer look at each individual concentration.

Have you ever thought about the trees in The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim? DigiPen BA in Game Design students learn their secrets early on in their studies. “There are reasons why the trees are where they are,” DigiPen level design instructor Bill Morrison says. “It always blows students’ minds.” In class, Morrison walks students down a pathway near the start of the game, leading from the humble hamlet of Riverwood to the majestic Nord capital of Whiterun. “You come around the corner and there are two trees on either side of the path. All of a sudden, from behind one tree comes the giant mead hall slowly sliding into view. Then the path goes straight and you have Whiterun right in the middle, gorgeously framed by these trees. It’s a beautiful, textbook reveal,” Morrison says. “Down the valley, you see one randomly placed tree between the path and the river, and once you get there, it actually provides even more framing!”

Deeply considering the placement of virtual trees is just one of the many duties of a level designer — game design’s most outward-facing discipline. “Level design is all about how to use the space the game takes place in, how to structure it so that it’s fun and interesting to move through, as well as pacing and varying the content so it’s consistently engaging and potentially emotional to play,” Morrison says. Level design often serves as a gateway for people’s initial interest in game design. “A lot of designers will tell you their favorite games growing up were ones that came with built-in level editors,” Morrison says. “Fooling around in those editors, level design becomes a touchstone for a lot of people on what game design actually is.”

Before DigiPen level designers start working with editors in an academic setting, they learn how to start breaking their ideas down using pen and paper. “First, you need to understand your goal and your constraints,” Morrison says. That means considering a laundry list of crucial questions like: What’s the level about? Where does it fit in the narrative arc of the game? Is there a character that needs to be introduced? A new gameplay mechanic? A new item that needs to be highlighted? What enemies are available to use at this point? After taking all of the above into consideration, DigiPen level designers begin blocking things out by sketching a simple top-down map. This is where spatial ideas start to take shape, gameplay flow is established, and encounters are developed. “Your pen-and-paper map helps establish a general plan. You start in a clearing, go down this path, encounter a crocodile near the river, then there’s an ammo pack and two guards with these patrol routes further down,” Morrison says.

In their introductory level design course, after learning pen and paper planning, DigiPen students quickly dive into a 2D platformer level editor to explore the next key components of good level design — pacing and variation. “Beyond learning how to use 2D space, it’s also a lesson in how many different ways you can create an increasing variety of encounters while maintaining cohesion,” Morrison says. It’s a skill he compares to music theory, likening enemy encounters to the notes in a song. “If it’s just fight one goblin, then fight one goblin, then fight another goblin, that’s going to get boring after a while,” Morrison says. “It’s one note.” Pure chaos, on the other hand, isn’t much better. “If you’ve got a bunch of random, unrelated challenges — an enemy, then a smashy wall, then fire traps — that usually doesn’t feel good either,” Morrison says. “You design a good level, and write a good song, by changing the notes, repeating notes, building on the patterns, and varying them over time.” Having a deep understanding of the mechanics and systems behind the game, much like knowing your musical instrument, is another important aspect of creating compelling levels. “Understanding that allows you not only to exploit those mechanics to design fun situations, it’s also important in making levels feel cohesive,” Morrison says.

You can walk into a room in BioShock and know exactly what happened there just by looking around.

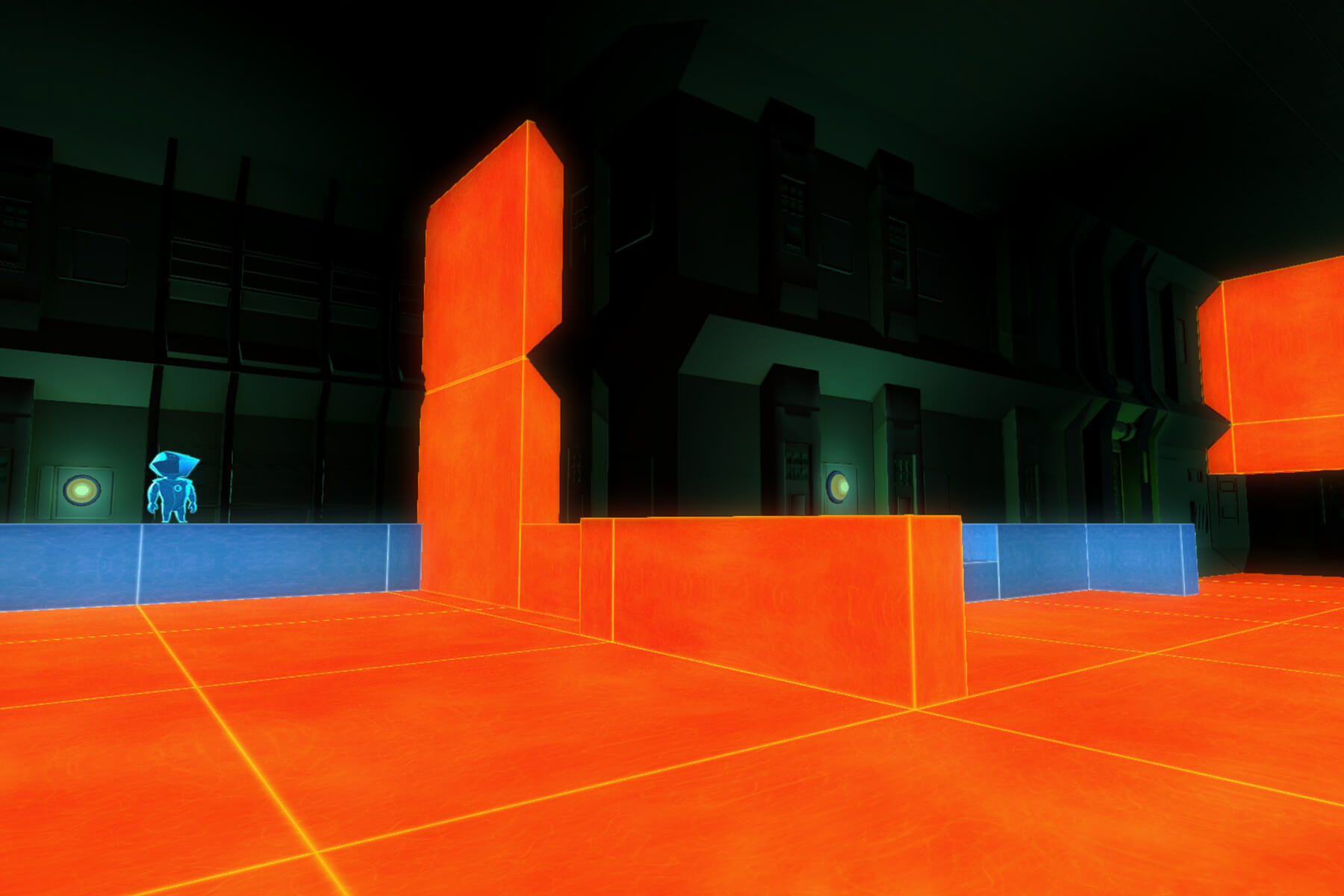

After working with 2D levels, students then move on to another crucial element of good level design — creating interesting spaces in three dimensions. “I will literally watch HGTV for my own level design research sometimes,” Morrison says. “Having a good grasp of architecture, spatial design, and interior design is really helpful in creating interesting 3D space.” Although level designers don’t create level art directly, they do lean into artistic principles by blocking spaces out with simple 3D geometry for quick iteration. In doing so, level designers learn how to manipulate color, light, shadow, and sight lines to draw players through their worlds. “Once you have that block mesh worked out and gameplay feels good in it, you can start working with your environment artists to make this giant white cube into the two-story, dilapidated bayou shack it’s meant to be in your level,” Morrison says. At DigiPen, students forego gameplay entirely in their first assignment with a 3D level editor. “We focus instead on creating a space that’s compelling just to walk through, leading players by transitioning through different environments and elevations,” Morrison says.

Eventually, students who choose to move up the level design concentration track begin to tackle narrative elements as well. “How do you tell a story if a player can go anywhere and do anything?” Morrison says. “You do non-verbal, environmental storytelling! You can walk into a room in BioShock and know exactly what happened there just by looking around.” Advanced DigiPen level designers also explore 3D puzzle design, linear vs. open-world design, single player and multiplayer level design, interior design, and more. “Even if students aren’t interested in specializing in it,” Morrison says, “I think game designers always have a certain attraction to level design, just because it’s the main way we experience games.”

DigiPen BA in Game Design student Brandon Stam on diving into level design:

“Growing up, whenever a game had a level editor, I would find myself in that more than the game itself. Halo’s Forge mode, for example. I loved to mess around and place vehicles in levels in interesting ways. I’d find a really cool mechanic and think, ‘How can I create a space that shows this off?’ Once I got to DigiPen, I found out that everything I’d been doing growing up had a title: level designer. I love that it’s about showing off every other game design discipline. Level design connects it all so the player can be guided to use those systems, to find those narrative story points, and engage in that user experience.

“I was particularly proud of my level design in my sophomore game team project. We made a top-down, competitive spaceship shooter for four players, featuring a high-speed bouncy ball players can ram into one another. It was a fun challenge thinking about how to build levels where players could engage with the ball in different ways. Some levels were built with curves and angles so you could do cool trick shots. Others were made with long pathways so the player could line up straight shots. Some levels were more tightly packed, so you would see players engage each other by shooting more, rather than going for the ball. Other levels were more open, so the ball would see more action. I tried to blend both of the game’s systems as much as I could for each level so they would fit all play styles.”

Related Articles in this Series