For the past decade, DigiPen faculty have built an impressive track record of guiding students in the creation of groundbreaking animated short films — films that often end up on the annual global festival circuit. But now, there’s a new buzzworthy film making the rounds that’s putting the talent of the DigiPen faculty itself — along with the film’s creator — front and center.

Directed by Seattle filmmaker Clare Chun, Shelter in Place is an animated short about a symbiotic relationship between a woman and her cat during the pandemic. It’s a film that explores themes of grief and isolation in a world that’s adapting to new concepts of day-to-day living and human interaction.

Unlike a traditional animated film, Shelter in Place was created using a method known as rotoscoping, whereby the animation was created by tracing over live-action footage in which Chun herself filmed and starred as the main character, co-starring with her real-life cat, Krystal.

Since its completion earlier this spring, the film has been getting noticed — including in France, where Shelter in Place recently made its European debut at Animation Day in Festival de Cannes.

“It kind of exceeded our wildest expectations,” Chun says.

For Shelter in Place, Chun’s production team featured the contributions of four DigiPen faculty members — chief among them Jazno Francoeur, director of the BFA in Digital Art and Animation program at DigiPen, who served as the film’s animator, editor, and production designer. He attended the Cannes screening in May with Chun.

The other DigiPen faculty contributors were Greg Dixon, assistant professor from the Department of Music, who mix mastered the audio; Chris Mosio, senior lecturer from the Department of Animation, who worked on footage assembly and color correction; and Lawrence Schwedler, program director for DigiPen’s music and audio degree programs, who wrote the film’s score. DigiPen alum Anoop Herur-Raman also contributed as a visual effects animator.

Multiple years in the making, the film project originated in 2019 as the brainchild of Chun. A professional actor for more than 10 years, Chun had parlayed her acting into filmmaking via live-action shorts and featurettes prior to discovering DigiPen as a possible collaborator. Inspired by live-action directors like Wes Anderson who had successfully ventured into animation, she wanted to direct and produce an animated film for her next project.

“I always want to make films that challenge me,” Chun says. “I don’t want to make the same film over and over again. There should always be versatility and growth.”

Moreover, she says, her earliest memories of storytelling came from animated content, partly the result of growing up in a Catholic and Korean home where she was mostly restricted to watching Disney films and cartoons.

“During college when I was directing one-act plays and student news shows, I had to really catch up on my film knowledge. My classmates chuckled when I found the horse head scene in The Godfather horrific,” Chun says. “My first theater gig was a musical Mack and Mabel playing Anna May Wong, and I remember referencing the singing in Disney movies because they were really good musicals, just animated.”

Chun’s original animated film idea was about a possessive cat who hisses and recoils at the idea of her owner, a man who has cared for her longer than any partner in his life, letting a new girlfriend move into their home. The idea was inspired by her own black cat named Penelope.

“I sketched storyboards for that film and wrote a script thinking originally the film should be a 2D or 3D animated film,” Chun says.

However, there was one issue: Although Chun was established in the Seattle film scene, she didn’t know any animators.

Undeterred, Chun began pounding the pavement by researching and cold calling animation production studios during her day job lunch breaks, eventually landing on DigiPen Institute of Technology, where many of the animation faculty had worked on several of the Disney features Chun grew up watching.

“I talked to a lovely lady on the phone where I gave her my brief bio of being an experienced actress, producer, and filmmaker in search of an animator for my next film,” Chun says. “I mentioned how I learned about storytelling through Disney films, and before I finished my sentence, she says, ‘You know, I have someone just for you.’”

It was Francoeur — himself a former Disney visual effects animator — who received the transferred phone call, and the two immediately struck up a friendly rapport. Still, with Chun wrapping up her third film project and Francoeur engaged in DigiPen’s overseas campuses, the timing for collaboration wasn’t quite right.

“I may have been in Singapore when she called the first time,” Francoeur recalls. “So we did this dance for quite some time.”

After almost a year of brief emails, the two finally met in person at a café near Chun’s apartment in December 2019. That’s when Francoeur looked over the filmmaker’s work in progress for the first time.

“She had boarded up this original story that was very similar,” Francoeur says. “It was interesting. … I thought, ‘You know, there’s something in this story.’”

It was shortly after that initial meeting when two events happened that dramatically altered the direction of the film. The first was the passing of Chun’s cat Penelope in January, leading her to adopt a new cat. The second, much larger in scope, was the arrival of COVID-19.

“I was observing the world being slapped with a huge pause button,” Chun says. “Everyone, including myself, was trying to establish our new normals in pandemic life: trying not to go batty from cabin fever, trying to keep in touch with friends over Zoom, fear of my day job income in a tanking economy.”

Meanwhile, Chun and Francoeur continued to hash out their ideas regarding story and production over FaceTime and Zoom calls.

I was observing the world being slapped with a huge pause button.

“We would have these conversations,” Francoeur says. “And then at one point, I told her, ‘It’s interesting. You keep telling the story about Penelope, but you’ve sent me pictures of this other cat that’s white.’ And she goes, ‘Oh, well, that’s Krystal. That’s my [new] cat. I sleep with her around my neck.’ I said, ‘Well, why aren’t you telling that story?’”

From there, a new storyline began to emerge, one that — according to Chun — explored how daily routines were lifesaving, physical contact was crucial, and how humans could learn a thing or two about unconditional love from their pets. It was the pandemic setting, she adds, that pulled these universal themes into focus.

With a solid story outline taking shape, there was still the matter of how to produce the film on a self-funded budget — in the middle of a statewide lockdown, no less.

“Any kind of animation can be very time intensive. … But being the person that I am, I usually like to think about what I call ‘benevolent cheating,’” Francoeur says. “I figured there’s got to be a solution somewhere that can leverage her ability, because she’s a director, she’s an actor, and she’s a writer.”

Referencing films like 2001’s Waking Life, Francoeur eventually suggested rotoscope animation as a potential solution. If Chun could direct and perform the live-action footage from the new storyboards, Francoeur could handle the animation.

“I said, ‘If you were to go that route, I could actually help you with the project, because then it’s not something where we would need a big crew,’” Francoeur says.

Fortunately, Chun knew just the person to contact, documentary cinematographer Dan McComb, who jumped on board to help film the project with Chun. Together, Chun and McComb filmed for seven months primarily from Chun’s own apartment, with Chun hopping in front of and behind the camera to make sure the acting movements and B-roll shots were ready for animation.

“It was just me and my cinematographer doing all of the roles that you would do on a regular film,” Chun says.

Francoeur tapped his own network at DigiPen as well, starting with Schwedler from the Department of Music. Although Schwedler had not worked on many film projects, his industry experience as a former audio director for Nintendo had involved scoring plenty of video game cutscenes and promotional trailers.

“It’s like short film scoring,” Schwedler says. “And scoring a picture is so much simpler than scoring a video game, because there’s a one-to-one correspondence between the frame and time.”

Still, he wasn’t convinced he was the person for the job until he decided to dive in one weekend by sketching out a rough score for one of the film’s midpoint sequences — a dreamlike interlude in which Chun had to film herself thrashing about underwater.

“When you’re scoring or writing music, it’s kind of like fishing, because you don’t know if you’re going to catch a fish right away or not,” he says. “I got lucky.”

His interpretation of the scene gave way to an ethereal piece of music sampling the sounds of an African plucked instrument and Bulgarian female choir voices, among other things. The reception was instantly positive, cementing Schwedler’s decision to commit to the rest of the project.

“So then we established a working relationship with Clare and with Lawrence in his mad laboratory,” Francoeur says. “It was just like pushing water downhill working with him, because he’s such a professional.”

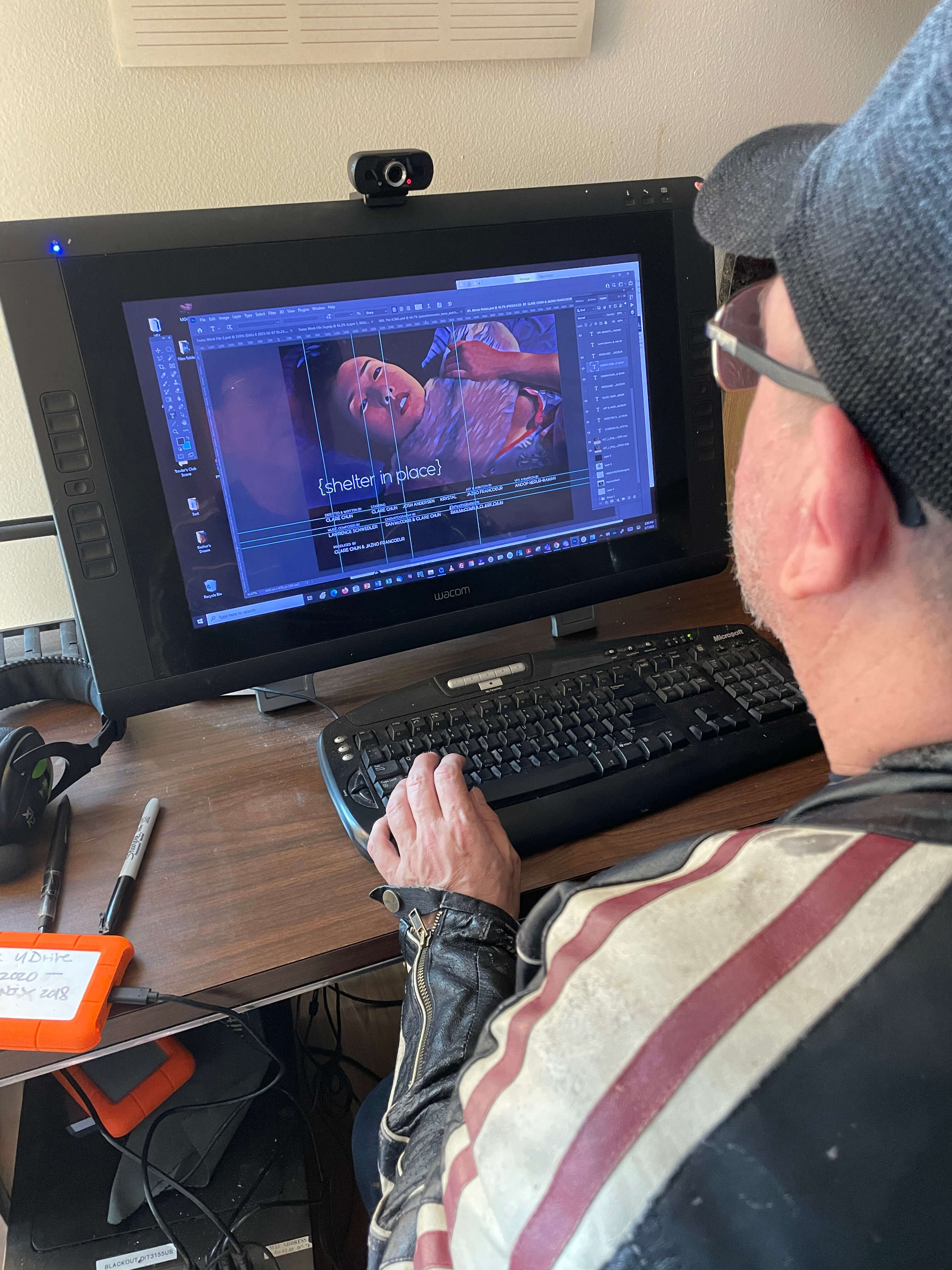

Despite Francoeur’s self-described motto of “benevolent cheating,” his actual experience on the project involved very few shortcuts. As the key animator, his task was to transform every single frame from the live-action footage into hand-drawn imagery, using Adobe Photoshop and little else.

“We always tell our students to scope down, so I did not take my own advice,” Francoeur says. “I took on the project because I knew it would take me way outside of my comfort zone, because I would be wearing hats I had never worn before.”

Having already screened at festivals in three countries, the film’s crew are crossing their fingers for continued success in other venues in the coming months.

“This was kind of what I like to call the little film that could,” Chun says. “You always want something like that to happen with your film, where you start with an acorn and it grows into a mighty oak tree.”

For Francoeur and Schwedler, the experience of making the film was even more valuable for the lessons learned, some of which have already spilled over into the classroom.

“As an instructor, you have to be learning every day,” Schwedler says. “Working on a project like this really let us do that, so I’m grateful to have been involved.”

Francoeur says he’s already started showing clips and production footage from Shelter in Place as teaching material.

“What matters at the end of the day is what ends up on screen, however you get there. So I’ve used this extensively in my lectures to talk about finding alternate ways of telling a story that are still innovative but won’t necessarily break the bank,” Francoeur says. “I can use it as a primer to help teach students, and I think it connects with them because they can say, ‘This is something my instructor did,’ as opposed to, ‘Oh, he’s just pulling this off of YouTube.’”